FOOD FOR THOUGHT FOR THE RELIGIOUS SKEPTIC

Even though only 54% of Americans said they were members of a church or synagogue in 2017, 87% said they believe in God, and a number of fairly recent polls say that between 70 and 80% believe in an afterlife. The Bible itself proposes a reason for this. Ecclesiastes 3:11 says that God has set eternity in the hearts of humanity. In other words, God has placed in humans the intuition that there is an afterlife and that it is eternal (without end). That explains why people have an interest in what will happen to them after they pass away. People also have a sense that the afterlife will either be a pleasant or a painful one, and that the pleasantness or pain of the afterlife will be related to how they spent their time on earth.

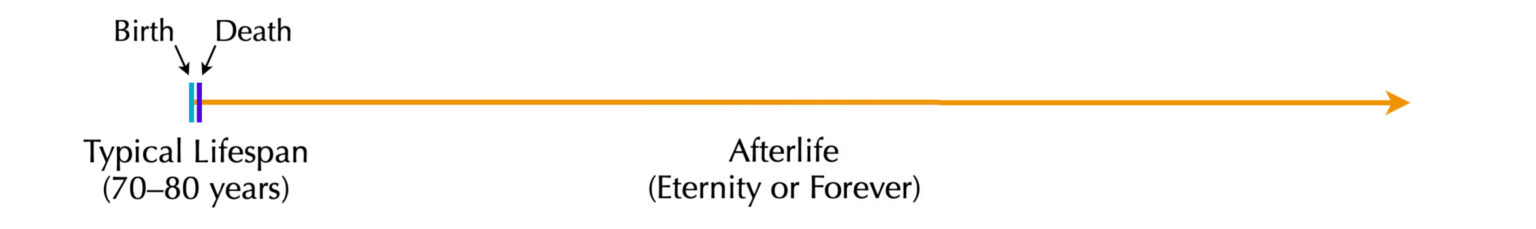

Even if such an eternal afterlife of happiness or misery is merely possible (not to mention if it is likely or an absolute certainty), that possibility makes religion the most important aspect of any person’s life:

This view of life impresses on us the words of Jesus himself, “What good is it for a man to gain the whole world, yet forfeit his soul?” (Mark 8:36).

Some might scornfully call this a “fear tactic,” but remember:

- Fear tactics are good, not bad, when the danger being discussed is real, or even just possible (e.g. think of how a good mother tries to make her toddler scared of the stovetop or the oven so that the toddler will not suffer a burn).

- The Bible doesn’t unsettle us with regard to the afterlife just to make us uncomfortable and leave us that way. God wants to point us to what Jesus his Son did for us, in order to make us certain about the afterlife and able to look forward to it: “The promise [of eternal life with God in heaven] comes by faith, so that it may be by grace and may be guaranteed…” (Romans 4:16).

Please talk to our pastor if you wish to learn more about the Bible’s message, so that you can have this certainty. You may be surprised to discover that Christianity isn’t just myths, fairy tales, and wishful thinking, but is firmly rooted in the facts of history.

Oxford professor and former atheist C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) once recalled how he had heard “the hardest boiled of all the atheists [he] ever knew” admit to him privately that the evidence for the historic factuality of the Gospels was surprisingly good (Surprised by Joy, 224). And it was the much earlier Oxford professor Thomas Arnold, one of the most renowned historians of his time and intimately acquainted with all sorts of ancient literature, who said in 1838 that he knew of “no one fact in the history of mankind [which was] proved by better and fuller evidence of every sort” than Christ’s death and resurrection from the dead (Christian Life, Its Hopes, Its Fears, and Its Close, 2nd ed., 15–16).

Come and see for yourself.